Covid hoaxes are using a loophole to stay alive—even after being deleted

Since the onset of the pandemic, the Technology and Social Change Research Project at Harvard Kennedy’s Shorenstein Center, where I am the director, has been investigating how misinformation, scams, and conspiracies about covid-19 circulate online. If fraudsters are now using the virus to dupe unsuspecting individuals, we thought, then our research on misinformation should focus on understanding the new tactics of these media manipulators. What we found was a disconcerting explosion in “zombie content.”

In April, Amelia Acker, assistant professor of Information Studies at UT Austin, brought our attention to a popular link containing conspiratorial propaganda suggesting China is hiding important information about covid-19.

The original post was from a generic looking site called News NT, alleging that 21 million people had died from covid-19 in China. That story was quickly debunked and, according to data from Crowdtangle (a metric and engagement product owned by Facebook), the original link was not popular, only garnering 520 interactions and 100 shares on Facebook. Facebook, in turn, placed a fact-checking label on this content, which limits its ranking in their algorithmic systems for newsfeed and search. But something else was off about the pattern of distribution.

While the original page failed to spread fake news, the version of the page saved on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine absolutely flourished on Facebook. With 649,000 interactions and 118,000 shares, the engagement on the Wayback Machine’s link was much larger than legitimate press outlets. Facebook has since placed a fact-check label over the link to the Wayback Machine link too, but it had already been seen a huge number of times.

There are several explanations for this hidden virality. Some people use the Internet Archive to evade blocking of banned domains in their home country, but it is not simply about censorship. Others are seeking to get around fact-checking and algorithmic demotion of content.

Many of the Facebook shares are to right wing groups and pages in the US, as well as to groups and pages critical of China in Pakistan and Southeast Asia. The most interactions on the News NT Wayback Machine’s link comes from a public Facebook group, Trump for President 2020, which is administered by Brian Kolfage. He is best known as the person behind the controversial We Build the Wall nonprofit. Using the technique of keyword squatting, this page has sought to capture those seeking to join Facebook groups related to Trump. It now has nearly 240,000K members, and the public group has changed its name several times— from “PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP [OFFICIAL]” to “President Donald Trump  [OFFICIAL]” then “The Deplorable’s

[OFFICIAL]” then “The Deplorable’s  ” and finally “Trump For President 2020.” By claiming to be Trump’s “official” page and using an imposter check mark, groups like this can engender trust among an already polarized public.

” and finally “Trump For President 2020.” By claiming to be Trump’s “official” page and using an imposter check mark, groups like this can engender trust among an already polarized public.

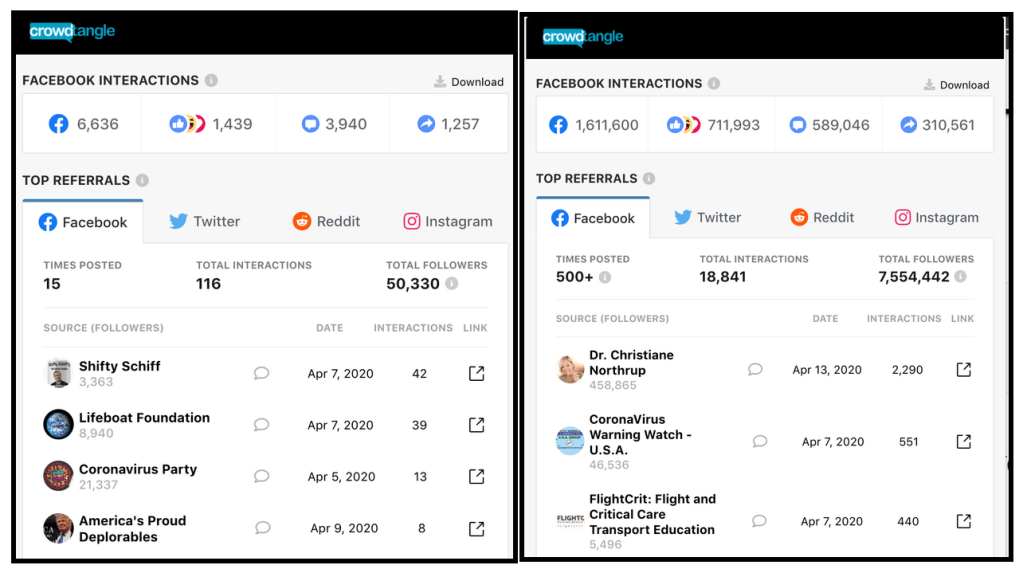

When looking for more evidence of hidden virality, we searched for “web.archive.org” across platforms. Unsurprisingly, Medium posts that were taken down for spreading health misinformation have found new life through Wayback Machine links. One deleted Medium story, “Covid-19 had us all fooled, but now we might have finally found its secret,” violated Medium’s policies on misleading health information. Before Medium’s takedown, the original post amassed 6,000 interactions and 1,200 shares on Facebook, but the archived version is vastly more popular—1.6 million interactions, 310,000 shares, and still climbing. This zombie content has better performance than most mainstream media news stories and, yet it only exists as an archived record.

Perhaps the most alarming element to a researcher like me is that these harmful conspiracies permeate private pages and groups on Facebook. This means researchers have access to less than 2 % of the interaction data, and that health misinformation circulates in spaces where journalists, independent researchers and public health advocates can not assess or counterbalance these false claims with facts. Crucially, if it weren’t for the Internet Archive’s records we would not be able to do this research on deleted content in the first place, but these use cases suggest that the Internet Archive will soon have to address how their service can be adapted to deal with disinformation.

Hidden virality is growing in places where Whatsapp is popular because it’s easy to forward misinformation through encrypted channels and evade content moderation. But when hidden virality happens on Facebook with health misinformation, it is particularly disconcerting. More than 50% of Americans rely on Facebook for their news, and still, after many years of concern and complaint, researchers have a very limited window into the data. This means it’s nearly impossible to ethically investigate how dangerous health misinformation is shared on private pages and groups.

All of this is a threat for public health in a different way than political or news misinformation, because people do quickly change their behaviors based on medical recommendations.

Throughout the last decade of researching platform politics, I have never witnessed such collateral damage to society caused by unchecked abusive content spread across the web and social media. Everyone interested in fostering the health of the population should strive to hold social media companies to account in this moment. As well, social media companies should create a protocol for strategic amplification that defines successful recommendations and healthy newsfeeds as those maximizing respect, dignity, and productive social values, while looking to independent researchers and librarians to identify authoritative content, especially when our lives are at stake.

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/3bPGZKh

Comments

Post a Comment